Designing the Unknown

What C-K Theory reveals about innovation

In my last (slightly rambling) post, I touched on C-K Theory as a powerful yet under-appreciated lens for thinking about innovation.

This blog focuses exclusively on C-K Theory, its mathematical foundations, and real-world applications. We will sees that the theory offers a perspective that encourages us to view ambiguity, uncertainty, and connections as essential elements for innovation.

A Theory Born from a Frustrating Truth

C-K Theory, short for Concept-Knowledge Theory, emerged because traditional innovation methods were failing. They performed effectively in addressing clear and defined problems but found it challenging when situations were complex and the issues were still evolving.

In the 1990s, Armand Hatchuel and Benoît Weil at École des Mines de Paris set out to change that. They discovered that innovations could be explained and modelled, initially naming their approach “innovative design” before formally introducing C-K Theory in a 2003 paper. They asked a deceptively simple question:

What if we stopped treating problems as fixed and started exploring them as evolving concepts?

This shift opened a new way of thinking grounded in rigorous mathematical foundations and design theory.

The Mathematical Foundations of C-K Theory

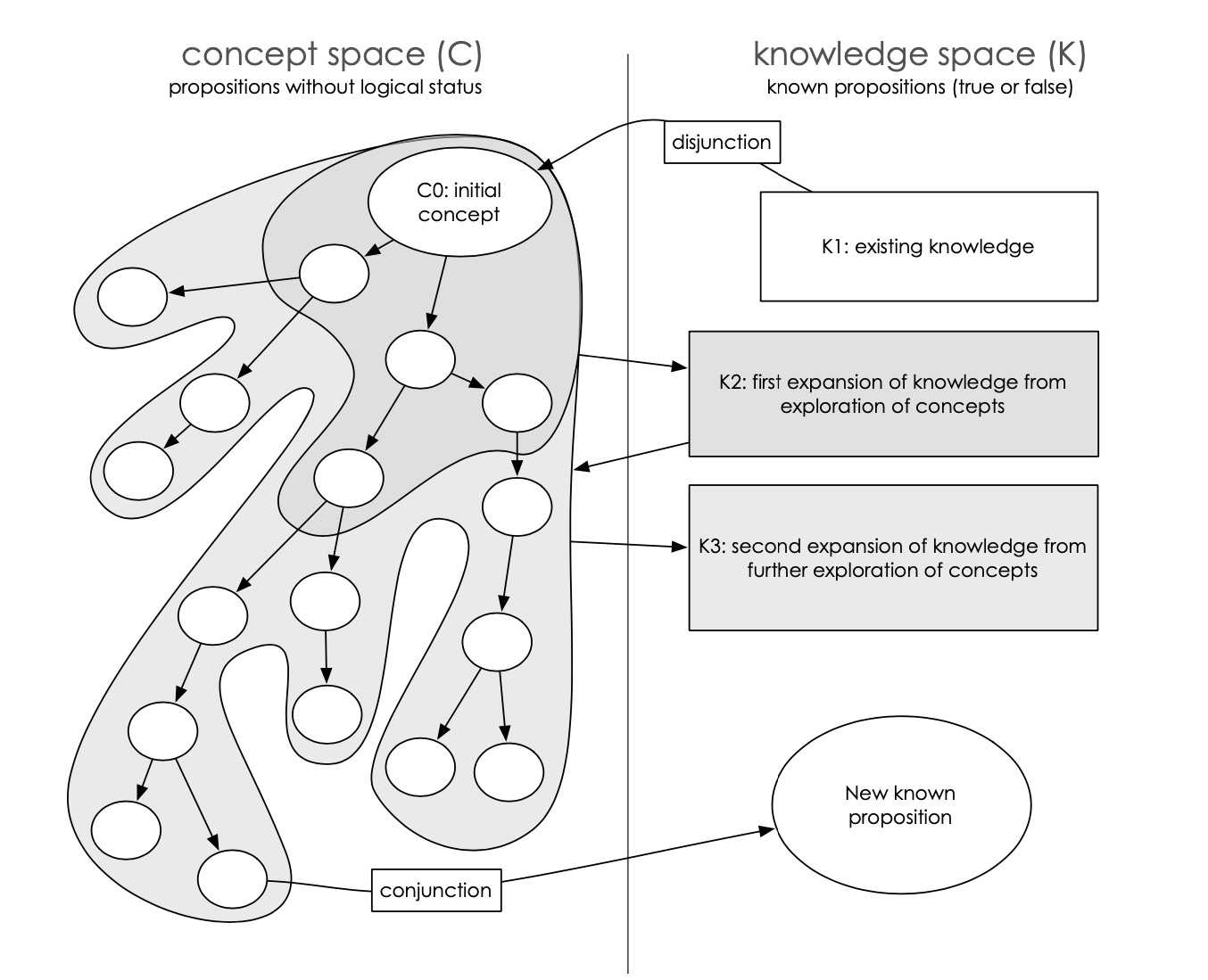

At its core, C-K Theory is built on principles from set theory and modern logic, mainly drawing from the concept of “Forcing” in set theory. It formalises design reasoning as a process of expansion, where concepts (C-space) and knowledge (K-space) grow dynamically through structured interactions.

The Knowledge Space (K-space) encompasses everything we know. It includes facts, data, and functioning models, which are elements that can be proven or disproven.

The Concept Space (C-space): Concepts in the C-space are undecidable propositions without a logical status in the K-space; they represent ideas that cannot yet be proven or disproven but hold innovation potential.

The mathematical underpinning allows C-K Theory to unify diverse approaches to design, from systematic engineering design to creativity theories, under a single framework. It also addresses foundational questions in design reasoning, such as how new objects or ideas can emerge from existing knowledge, a process that traditional problem-solving methods often overlook.

Unlike other frameworks that treat design as optimisation or problem-solving, C-K Theory positions it as a logic of creation, a way to explore the unknown rigorously. C-K Theory addressed three limitations of existing design theories: their inability to account for innovation, domain dependence, and separation from creativity theories.

Innovation as a Balancing Act Between Knowing and Imagining

What makes C-K Theory powerful is the distinction between concepts and knowledge and how they interact in what the theory calls a “double expansion” of both spaces.

The theory describes four “operators,” which are essentially methods for navigating between and within these spaces:

C → C: We cultivate an idea by splitting, mixing, and reshaping it until something fresh forms.

C → K: We test it, ground it, and turn it into something we can know.

K → K: We enhance the knowledge base through research, discovery, and deeper inquiry.

K → C: A fresh perspective based on existing knowledge can inspire an entirely new idea.

It’s not a straightforward process. It loops and zigzags. Sometimes, it stalls, and that’s often where new potential unfolds.

Instead of rushing to solutions, we stay with the questions for a while longer. We push the boundaries of our understanding, and in doing so, we open the door to breakthroughs.

The Benefits of Working This Way

C-K Theory encourages teams to explore ideas deliberately and thoughtfully, bringing several key advantages:

Avoiding premature convergence - This framework discourages settling on the first plausible solution, allowing teams to explore a broader range of possibilities.

Surfacing invisible assumptions - C-K emphasises naming and addressing assumptions that might otherwise go unexamined.

Balancing creativity with structure - While it encourages wild ideas and imaginative thinking, C-K provides a structured approach to ensure those ideas are focused and actionable.

How to Apply C-K Theory in Practice

C-K Theory may sound abstract, and it is. But that abstraction is part of its strength. It gives us a flexible structure to navigate uncertainty, not by forcing solutions but by expanding the space of possibilities. Whether designing policy, building products, or leading strategy, C-K offers a structured way to reframe challenges and stretch beyond what’s already known. Here’s how you can start:

1. Define Your Knowledge Space (K-space)

Start by mapping out what you already know about the problem or domain, facts, data, models, assumptions, and all the elements that form your current knowledge base.

2. Explore the Concept Space (C-space)

Shift focus to imagining possibilities beyond current constraints:

What ideas seem impossible today?

What assumptions could be challenged or reframed?

What new combinations of existing knowledge might create something novel?

3. Use the Four Operators

Leverage the operators (C→C, C→K, K→C, K→K) iteratively to expand both spaces dynamically.

4. Facilitate Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Use tools like KCP (Knowledge-Concept-Project) workshops to bring diverse teams together for co-creation. The KCP method structures collaborative innovation by building shared knowledge, exploring concepts, and developing concrete projects.

5. Pair with Complementary Methods

Combine C-K with Design Thinking or Systems Mapping for user-centric framing or understanding interdependencies.

6. Stay Comfortable with Uncertainty

Embrace ambiguity as a space for discovery rather than rushing toward premature solutions.

Real-World Applications of C-K Theory

Several major organisations have successfully implemented C-K Theory in their innovation processes:

Aerospace Applications

A European laboratory working with ESA and CNES applied the C-K Theory to Mars mission design, specifically exploring Mg-CO2 combustion systems that use the Martian atmosphere as an oxidiser. This approach helped them avoid traditional reverse engineering methods and instead use a “breadth-first” strategy to explore innovative propulsion concepts during early design phases.

Smart Tools Development

The start-up Avanti used the C-K Theory to expand beyond its initial nail holder product. When faced with numerous potential directions (hand protection, fore-hole, pliers), they applied C-K reasoning to reframe their concept of “nail holder” as a broader product type. This led to a “smart-tools” design strategy focusing on easy-to-use, affordable, and innovative tools that sustained the company’s growth.

Corporate Innovation

Thales Group is among several major companies (including Renault, Dassault Systèmes, and RATP) implementing C-K Theory in their innovation processes.

Water Management Policy in Apulia, Italy

Researchers used a C-K Theory-inspired framework called C-K E/I to analyse innovative policy solutions for water management problems in the Apulia Region of Italy. This approach helped to:

Formalise the policy design process

Generate previously unimaginable alternatives through the co-evolution of knowledge and concept spaces

Bring together experts and institutional and non-institutional actors to find new ways of collaboration

Overcome the dichotomy between expert and non-expert knowledge

Support overcoming fixation phenomena and facilitate group learning processes

This example demonstrates how C-K Theory principles can adapt to support innovative policy design in complex environmental management contexts.

Consumer Products

While not explicitly attributed to C-K Theory, 3 M’s development of Post-it Notes illustrates the theory’s principles in action. The eventual success of Post-it Notes came not from solving a predefined problem, but from rethinking what “failure” meant. This reclassification of a “non-sticky” glue into a new product category is classic C→K reasoning; an idea becomes knowledge through reinterpretation.

It’s Not a Plug-and-Play Toolkit

C-K Theory isn’t a silver bullet. It demands intellectual investment.

Its formal structure and abstract nature resist casual implementation. It thrives with skilled facilitation and proper training and works well with complementary methods such as Design Thinking, Systems Mapping, Foresight, and Agile.

Consider it a framework or scaffolding for thought, not a prescription. It serves as a means of creative expansion, not just a way to solve problems. This perspective enables us to view innovation as a space of potential, not as a linear pipeline. It shifts our focus from addressing established problems to shaping concepts. This change influences how you lead, frame challenges, and create an environment accommodating the unknown.

So Why Does This Matter Now?

We are living in a time when certainty is a luxury.

AI is advancing more quickly than our governance frameworks can keep up with. Climate change is altering every system we rely on, social contracts and the global order are changing rapidly. In this context, innovation can’t just be about better execution.

It has to be about deeper exploration.

C-K Theory provides a structured approach that emphasises clarity and acknowledges the complexity of our world. It invites us to move beyond “fixing” and into creating not just new answers but also new questions.

At its heart, C-K Theory is a philosophy for navigating ambiguity, exploring what we do not yet know how to define.

An Invitation to Think Differently

So here’s my key takeaway. C-K Theory is more than just a framework; it embodies a mindset, reminding us that innovation starts with curiosity, not certainty.

If you’re leading teams, designing strategies, or grappling with a complex challenge, consider this:

What if the problem isn’t clearly defined yet? What if your role isn’t to solve it but to shape it?

What would change if you started there?

I will continue investigating this topic, exploring the connections with futures and foresight more deeply soon.

Keep exploring.