It’s been a while since I captured thoughts in words, the tension has been building but the habit has remained elusive in the face of a period of intense learning. The Christmas break provided a brief pause, and this coupled with ramping up training for my next ultra provided space for thinking and reflection. The hiatus is over and I’m back to share my reflections, most recently from the collision of recent participative futures workshops I designed and delivered, and the discovery of stickiness and friction.

It’s a surprise how rich, intense and insightful physical workshops can be. While I have a strong intuition that the physical format, the movement and engagement with artefacts and guiding structure create the conditions for deeper dialogue and sensemaking, leaving participants with renewed thinking, insights and perspectives, I’ve struggled to put my finger on how or why? Is it just magic?

I recently picked up Thomas J. Chermack's Scenario Planning in Organisations. The authors description of stickiness and friction in knowledge exchange, particularly within the context of participative, interdisciplinary scenario planning led to a lightbulb moment, providing an anchor for the something I struggled to externalise.

Exploring 'Stickiness' in Knowledge Transfer

The concept of stickiness as illuminated in the book, delves into the challenges of transferring information across diverse groups or individuals, particularly where this concerns complex and specialised information. Chermack, drawing on the insights of Ford & Sterman (1998) and Von Hippel (1998), articulates that this difficulty is not just a barrier but an essential component of the learning process. Importantly, this process involves a significant cost – not just in financial terms, but in the effort, attention, and resources required to effectively transfer and internalise complex information.

In the context of participatory workshops, where diverse teams engage with future scenarios, the concept of stickiness becomes particularly salient. Participant teams are not just passively receiving information; they are actively grappling with, interpreting, and making sense of scenarios and others' interpretations. This process challenges their assumptions, beliefs, and perspectives, demanding a high level of attention, engagement, and effort – the very cost associated with overcoming information stickiness. According to the feedback I've received, this translates into a rewarding, albeit hard-earned, social learning experience.

Now let's consider the nature of scenarios as a tool in these workshops. They go beyond presenting a set of potential futures; they serve as a canvas for imaginative exploration and creative interpretation. Participants are encouraged to think beyond the given information, challenge existing assumptions, and incorporate alternative narratives and perspectives based on others knowledge and worldview. This active engagement between scenarios and teams helps unlock and transfer knowledge among participants, revealing new insights, identifying blind spots, and fostering a more nuanced understanding of the complexities and uncertainties that shape our future. Through this intense process, scenarios go beyond being just stories and become powerful tools for strategic thinking, planning, and ‘unsticking’ individual knowledge and perspectives.

While Chermack posited scenarios as a tool for reducing the stickiness of information by facilitating easier transfer and shared understanding, my observations in these workshops suggest an interesting nuance. The intensity of focus and effort that scenario exploration demands can, in fact, increase the 'stickiness' of new information and knowledge learned by individuals during the process. It's this heightened stickiness, born out of the cost of engagement and processing, that has the potential to change narratives and influence the potential for change.

When I contrast this with the experience of an online virtual workshop, using tools like MIRO, the differences are stark. The trade-off between effort and convenience is clear. In some situations, the physical workshop experience, with its tangible interactions, non-verbal communication and immersive engagement, is a powerful means for creating 'stickiness' while also ‘unsticking’. I hypothesise that this paradoxical effect enhances the likelihood of lasting impact and downstream change.

In essence, stickiness in knowledge transfer is not just about the information shared but how it is engaged with, processed, and internalised. This understanding (or maybe misunderstanding?) is growing as a cornerstone in my approach to designing participatory interventions, where the goal is not just to inform but to inspire and transform.

The Role of Friction in Decision-Making

Chermack's description of friction, contrary to the pursuit of streamlined, efficient processes, highlights its essential role in decision-making, especially in collaborative settings. It's the diversity of viewpoints, small disagreements, creative tensions, ethical considerations, and other perspectives that introduce necessary pauses, leading to more thoughtful and comprehensive discourse and decisions.

In the age of AI, this concept of friction becomes even more critical. As technology increasingly automates decision-making processes, the natural checks and balances provided by human interactions – the very essence of this friction – are at risk. This reduction in friction could lead to an increase in decision failures, as automated systems lack the nuanced understanding and ethical considerations inherent in human judgment. Therefore, maintaining a balance between technological efficiency and human insight is crucial to preserve necessary friction in decision-making.

I find these insights from the last millennium to be remarkably prescient, as they align with the current state of AI and emphasise the need for a more balanced and somewhat symbiotic relationship between human judgment and technological advancement.

Why Friction is Beneficial in Participative Futures Thinking

When exploring future scenarios, participants from diverse backgrounds bring their unique knowledge, perspectives, and experiences to the table. This diversity creates friction, as each participant may have different views and assumptions about a given scenario and varying ideas on priorities, the implications and how to address them.

For example, technologists may emphasise the role of emerging technologies, while environmentalists may focus on sustainability challenges. Some may hold a techno-optimist worldview, while others may have a contrasting techno-pessimist perspective. Reconciling these diverse viewpoints not only adds depth to the discussions but also counters groupthink and surfaces a broader array of potential developments and challenges.

Moreover, this friction is not just beneficial for the richness of discussion; it is crucial for building true expertise. The experiential elements and social interactions that come with this friction are what develop deep understanding and nuanced judgment in organisational decision-making. In this way, participative futures thinking, with its inherent friction, becomes a rehearsal ground for possible futures, building anticipatory awareness and the opportunity to incorporate this into strategic thinking and processes.

These insights coupled with the challenge of processing and articulating them, mean the concepts of stickiness and friction will be at the forefront of my mind when designing the next intervention. I guess something has stuck!

And lastly, I cannot escape the irony that these reflections are tainted by my own world view, biases and assumptions. Such is the wonder of being human.

Further Avenues of eXplorulation

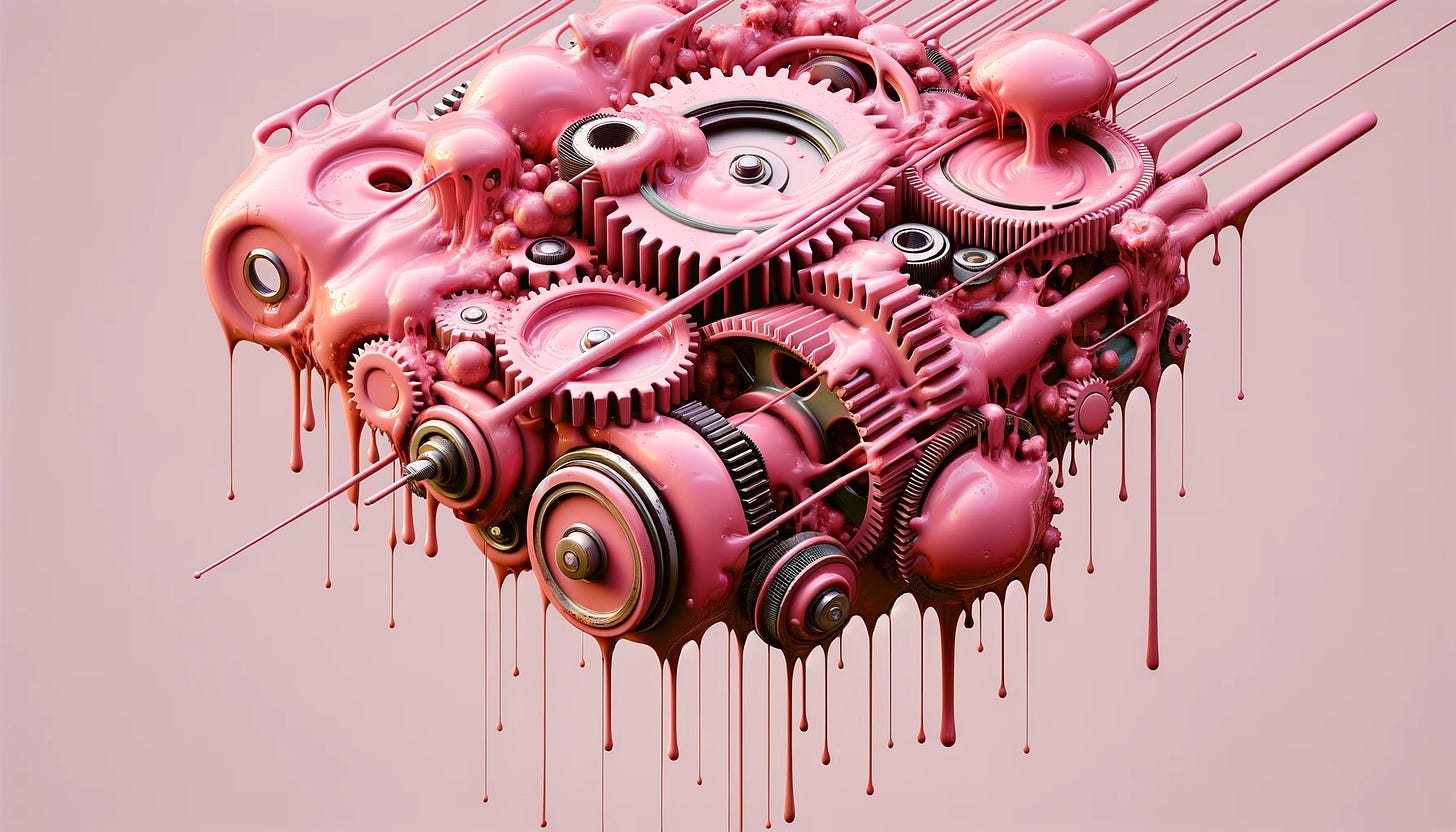

The process of unpacking these insights and thoughts, drafting this article, engaging the services of AI (as a tool), and revisiting the book has involved a significant amount of friction and 'unsticking' of ideas. It's no surprise, then, that this process leads to new insights and questions, a phenomenon I liken to 'nucleation' – drawing inspiration from some work I did around micro-bubble nucleation many moons ago.

This metaphor represents the sudden and dynamic emergence of new ideas and perspectives around a given inspiration, much like bubbles forming in a fluid around an impurity. In a way, this mirrors the 'stickiness' and 'friction' inherent in our cognitive processes – the way new ideas coalesce and take shape, often in unexpected ways. I will continue to explore these concepts, and anticipate that this 'nucleation' of ideas will guide me into new areas of thought, speculation and the occasional eXplorulations blog.